Wrong fork in the road: the problem with human exceptionalism

Trying to reconcile Western Science with Aboriginal Cosmology

The earth is the forgotten basis of all our awareness – David Abram from: Spell of the Sensuous (1996).

“If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern,” (The Marriage of Heaven and Hell by William Blake (1790)).

1. Anthropomorphism

For me, the word ‘anthropomorphism’ exemplifies our belief that humans are the pinnacle of evolution and deserve special status. The conventional definition of anthropomorphism is the attribution of human characteristics to a god, to animals, to plants or to things. In previous posts, I have described some plant behaviors that defy easy explanation. The more I accept that these inexplicable things come from the conscious decisions plants make the less confounding the actions are to me. Being conscious means making decisions and sometimes doing the counterintuitive thing even when the outcome is far from certain.

‘Anthropomorphism’ relies on an inherently bad premise, as if what we humans feel and do are somehow brand new to this world. Anthropomorphism doesn’t even deserve the status of being a word, unless it is as the description of a particular kind of philosophical error. To think that our feelings and actions are the models or aspiration for all non-humans could not be more ass-backwards. We did not usher emotions nor consciousness into this world. We inherited a world already well alive with both.

2. The problem with religion and science

In Genesis 1:26, God says, “and now we will make human beings; they will be like us, they will resemble us. They will have power over the fish and birds and all animals, domestic and wild, large and small.” But God also asks us to take care of the Earth - as his creation. We, represented by Adam and Eve, are “given” the run of the place and head of household status. But immediately afterwards, Adam and Eve are ‘tricked’ and take a bite of the apple from the Tree of knowledge (Tree of Self-Knowledge). Suddenly they recognize they are naked. Our separation from the rest of the earth had begun.

Over time for many in the West, scientific “theories” have overtaken religious stories as the dominant way to understand this world, to best “actualize” the practice of living. Science built its edifice and toyed with the notion that it alone is objective. Somewhere along the line, many of us fell in love with out intellect and replaced religious beliefs with scientific ones.

Descartes voiced the belief (fear?) that the only thing he could be sure of in this world was his own interior monologue – cogito ergo sum. The idea of a Platonic ideal, a life everlasting in a land of mathematical perfection brings a kind of magic to the short time we get to think about these things. The edifice of western science was quietly built with the same bias about our clear superiority as western religious belief was. Western science reinforces the bias.

Leave it to us humans to create an inherently destructive “Us vs Them” story in a world where beauty and strength are built through community, reciprocity and shared history. With perhaps the exception of a few sensitive or crazy souls, western society has systematically and wantonly tried to bury indigenous cultures and their stories that do not divide people from everything else. I think the two biggest issues we have with these cultures and their stories is that they refute the myth of human exceptionalism and appear to be anti-progress, anti-modernity.

I think our exclusivity and modernity stories come from our belief that evolution and progress always operate in the same direction. We humans must be best, one might reason, because we’re the most recent evolutionary development. But we know from experience the world operates in a less straightforward fashion. We all make mistakes and sometimes we regret them. A mistake can be hammered into the ground, forgotten or hidden, and still persist as a mistake.

3. Indigenous Cultures

The ancient cosmologies of indigenous cultures around the world didn’t start out by separating humans from the rest of the living earth. Just the opposite. These older cultures recognize humans as just one of the many different kinds of people (tree people, rock people, star people, etc.) woven into a network of living things that coat the earth. These indigenous stories focus on commonalities and our mutability into and out of everything else.

I’m going to use the cosmology of the Aborigines of Australia, as the example here. I still have so much to learn about these other cultures. This is just a starting place for me, for now.

The foundation of Australian Aboriginal culture is based on the remembrance of the origin of life. In the Aboriginal world view every meaningful activity, event or life process leaves behind a vibrational residue in the earth, like plants leave an image of themselves as seeds. The shape of the land – its mountains, rocks, river beds and waterholes – and its unseen vibrations echo the events, that brought that place into being. As with a seed, the potency of an earthly location is wedded to the memory of its origin. The Aborigines called this potency the “dreaming” of a place and this dreaming constitutes the sacredness of the earth (Voices of the First Day, Lawler, 1991).

All creatures – from stars to humans to insects and beyond– share in the consciousness of the primary creative force and each in its own way mirrors a form of that consciousness. In this way the “dreamtime stories” perpetuate a unified world view. This unity compels the aborigines to respect and adore the earth as if it were a book imprinted with the mystery of original creation. To exploit the earth was to exploit oneself (Lawler, 1991).

For the aborigines, the form of each thing was itself an imprint of the metaphorical or ancestral consciousness that created it. It is through the earth itself that language of the primal seed speaks through time. The dreamtime myths guide the Aborigines to see the physical world as a language (Lawler,1991).

4. How Western Science now supports these indigenous cosmologies

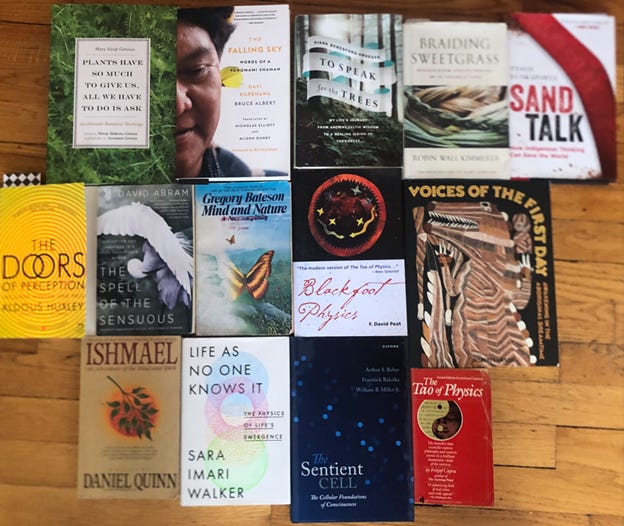

This work is hardly the first attempt to reconcile “modern” western science and indigenous cosmologies. Fritjof Capra, in the Tao of Physics (originally published in 1974) and F. David Peat in Blackfoot Physics (2002) both demonstrated, I think, that quantum physics is a western scientific story finally capable of understanding these older stories.

Quantum physics blew up our classical, deterministic understanding of the world. The uncertainty and mystery of instantaneous connection without time or space impediments imbues the world with a new kind of magic. Now the scientist - the watcher just watching - changes outcomes. There is no such thing as true objectivity, it is gone in a flash.

A new breed of physicists and biologists are now offering interpretations of life and consciousness that to me, at least, are as equally mind-blowing as quantum physics. These new theories recognize and in a sense, honor, the origins of life and consciousness in strikingly similar terms as these older cosmologies.

Sara Imari Walker, an astrobiologist and theoretical physicist at The Beyond Center at Arizona State University says that memory in complex living and non-living objects is physically instantiated – it is part of the architecture. The parts of a complex object come from and point to their origin from other objects. The information about the steps of their formation must exist in these other objects.

This means the physical algorithm is the object and molecules are threads through time. The way of building an object is the object. Lineages are objects and objects are lineages. Lineages of information propagating through time and matter is what it means to be alive. Lee Cronin, a close collaborator with Walker, puts it this way: “Life is the universe making a memory” (Life as No One Knows It, Amari, 2024).

Consciousness is and was part of this legacy long before humans arrived. We are just at the backside of a long line of consciousnesses. Lynn Margulis made the case in The Conscious Cell (2006) that everything is conscious at least down to the cellular level. She showed that unicellular organisms combined via symbiogenesis to produce the first eukaryotic (multicellular) species and life has reconstituted itself as an amalgamation of individuals all the way up ever since.

Those first unicellular organisms were conscious. Unicellular organisms have valenced experiences, learn, form surprisingly stable memories, communicate meaningfully with each other and are capable of decision-making and problem solving. Every form of life is not merely conscious in some vague way, say Reber, Baluska and Miller (The Sentient Cell, 2023) but is specifically capable of self-referential experiences.

All conscious beings are also “error-prone”, express doubt at an internal self-referential level as they analyze and act on incoming information. As Reber, Baluska and Miller say, we all live with “obligatory ambiguity”. I think this is the price for free will.

Without sentience, they argue, those first living organisms would have been evolutionary dead ends unable to survive in the chaotic, dangerous environment in which life first appeared. In CBC theory, sentience is viewed as a continuum where each emerging version is a new variation on mental expression and has its evolutionary foundations, its roots, in the functions and forms expressed in the species that preceded it. “Nothing,” Margulis said “has ever been lost without a trace in evolution.”

Gregory Bateson, the genius scientist-philosopher, called this imprint, this language, this vibration, the “pattern that connects” (Mind and Nature,1979). While this phrase may seem trite at first, his argument is built with descriptions, connections and dialogues (“we-two” yarning) about anthropology, sociology, epistemology, genetics, embryology and language. I have read this book over and over dozens of times and still feel like I still don’t quite understand its deepest, subtlest points. It is as if he is pointing towards what needs to be said but cannot be put into words.

This pattern connects things that grow up together simply because they are participants in the same story, woven together through space and time. The story of life is also written in DNA. The shapes of animals and plants are transforms of messages that connect via lineage. Anatomy must contain an analogue of grammar because all of anatomy is a transform of message material (Bateson, 1979).

This algorithm/lineage/patten also connects people because they think in terms of stories. As Bateson says: “…thinking in terms of stories does not isolate human beings as something separate from the starfish and sea anemones, the coconut palms and the primroses…..thinking in terms of stories must be shared by all….minds, whether ours or those of the redwood forests and sea anemones.” (Bateson,1979).

5. Being conscious & knowing everything else is too

In order to live with our western stories, we need to hold fast to the illusory distinction between ourselves and the rest of the living world. Aldous Huxley in his 1954 book, The Doors of Perception describes his “altered reality” after ingesting a half gram of mescalin. The mescalin, he said, did not create a vivid, hallucinogenic inner life, but rather revealed the stunning vitality of the external world. Huxley surmised that the human brain of us language users does more work to throttle down the inescapable wonder of this world than to allow it in. For Bateson….. “It is as if the stuff of which we are made [is] totally transparent and therefore imperceptible, and {it is] only appearances of which we can be aware [as] cracks and planes of fracture in that transparent matrix,” (Bateson,1979).

There is an almost a hallucinatory effect ahead for you once you start dropping the ingrained, western ways of thinking. If everything has an interior life, then we are truly interacting with everything, including all non-humans, every day all the time. Instead of blocking off or holding back the thoughts and feelings of all these interactions what if we embraced them?

Allowing the whole living world in all the time, Huxley speculated, would render its recipient unable to act because they would be so interested in simply taking it in. “By denying the universe an internal life,” Robert Lawler writes, “we imprison our own awareness so that we live only in the shallow surface of the world”.

6. Healing the ‘Anthropomorphic’ Divide

We have lost the our sense of parallelism and shared legacy with plants and animals. We need to recover the feeling of unity between us and the rest of the biosphere. A clear theme from all these older stories is that the future is grim for the takers of this world, who ignore our fundamental interconnectedness and limitations. In a world of limits you cannot extract everything and expect to have something left at the end.

Davi Kopenawa, a Yanomami shaman put it this way about the Amazon (though it might as well be about the entire planet): “The forest is alive. It can only die if the white people persist in destroying it. If they succeed, the rivers will disappear underground, the soil will crumble, the trees will shrivel up and the stones will crack in the heat. [Shaman] will not be able to repel the epidemic fumes which devour us. They will no longer be able to hold back the evil beings who will turn the forest into chaos. We will die one after the other, the white people as well as us. All the shamans will forever perish. Then if none of them survive to hold it up, the sky will fall” (The Falling Sky, Davi Kopenawa and Bruce Albert, translated by Nicolas Elliot and Alison Dundy, 2015).

I am not anti-humanist and I am not suggesting we all need to return to some “primitive”, prelapsarian past. What I am suggesting is that the veracity of a story should be not be solely judged by where it falls on the continuum of modernity, but rather the degree to which it helps sustain life and meaning. The story of human exceptionalism is the myth that fuels our unfettered exploitation of our non-human kin, our shared ancestors and our basis for mutual existence. Perhaps, the story of modernity does not have to be about unlimited growth and progress, but rather growth and progress that takes into account the rest of the living world’s needs at the same time as considering ours.

Despite the odds, the path my western ancestors did not take has been maintained by indigenous people. We need to step off our white people podium, acknowledge we are not the masters of this world and go back to that old fork in the road. We need to re-engage much more sympathetically with everything else. We need to care for the entire living world, as much as we can, as if all living things were related, because hey are. We have to figure this out and soon if we hope to prove that our brand of consciousness is not just some evolutionary dead end.

(With a big shoutout to one of my best friends: Dave Blake for his very helpful thoughts and edits)

Some suggested reading:

Watching "Roots of the Sky" shift from a highly technical view of nature to this more holistic view has been fascinating. The shift is within you, right? Something has changed, has caused the change. I very much enjoyed this.

Excellent read, thank you!